Four Ways Disaster Risk Finance Strengthens the Effectiveness of Adaptive Social Protection

COVID-19 will hit the poorest the hardest. Estimates show that by the end of the current crisis, the pandemic could push up to a 100 million people into extreme poverty. Poor and vulnerable households are often forced into negative coping strategies that have long‐term, irreversible, and intergenerational effects. This crisis and the unrepenting risk of other seasonal disasters, such as floods and droughts, once again highlight the need to build systems that strengthen resilience within the poorest communities ahead of the shock.

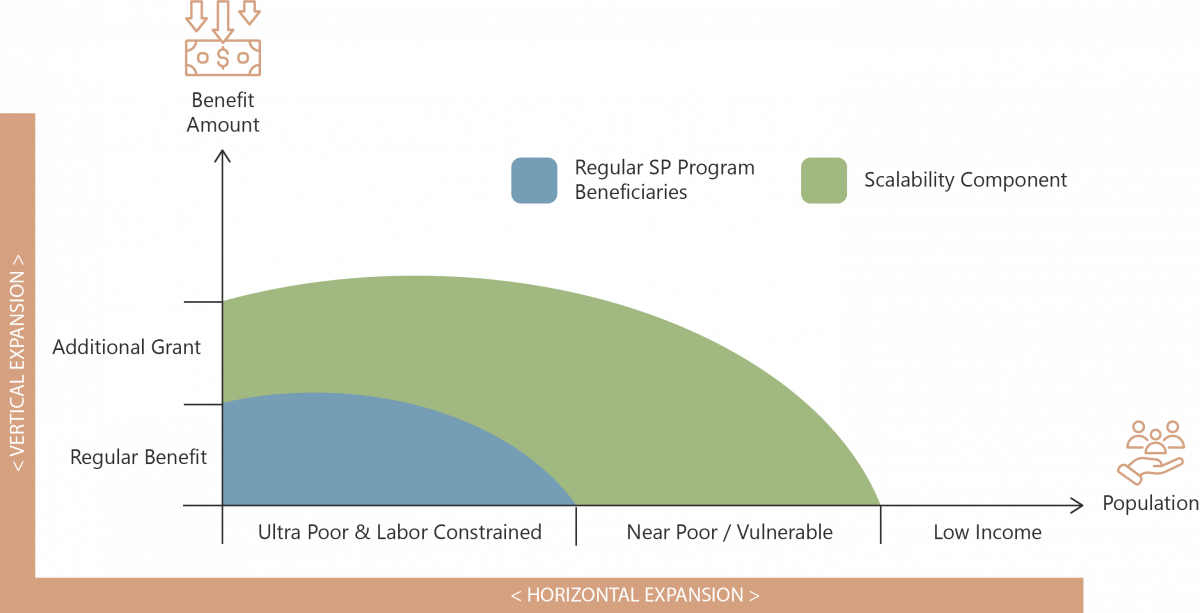

The good news is that this negative cycle can be broken. Experience shows that social protection (SP) systems combined with sound financial risk management instruments can be leveraged to build household resilience to those kinds of shocks by providing timely assistance to vulnerable households. This is often offered referred to as Adaptive Social Protection (ASP). To adapt, the systems commonly expand vertically by offering greater assistance to existing beneficiaries, or horizontally by using program systems to provide assistance, or both. This approach is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Adaptive Social Protection—Horizontal and Vertical Expansion

Source: Shock-Responsive Social Protection Systems Research, O’Brien et al., 2018.

There is a growing body of evidence about the multiple benefits of a timely response to shocks. SP safety nets can serve as a conduit to deliver financing mobilized through the right mix of disaster risk financing instruments to the most vulnerable. A Disaster Risk Finance (DRF) approach helps governments secure adequate funding for safety nets at the lowest cost, including in the case of disasters. Concretely, a DRF approach to ASP can increase the speed, predictability, and effectiveness of response by prepositioning triggers and finance and by pre-identifying beneficiaries. DRF can strengthen both the ability of governments to (a) finance the scale-up costs (money-in) and (b) provide timely funds to the most vulnerable (money-out).

The DRF principles draw on lessons learned from the private sector and are akin to the market-based principles used in the financial, banking, and insurance sectors. Thus, the principles require expertise in data analytics, underwriting, and catastrophe, actuarial, and capital modeling.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the need for plans that have flexibility in both money-in and money-out so those processes can enable a response to the unexpected.

How DRF Strengthens the Money-out Process

Irrespective of where the finance comes from, if one is to avoid delays in the release of funds, pre-agreed procedures and protocols are needed so the funds can be transferred to ministries or departments that operate the SP program and then can be disbursed to the beneficiaries.

1. Prepositioned Triggers for Response

Understanding and quantifying the risk is key to ensuring that the right instruments are in place. An approach similar to the one used by the insurance sector is required, first by modeling the risk and then by assessing appropriate triggers for response. This is an iterative process as the decisions made on the design of the mechanism have an impact on funding needs. An open and transparent approach will help decision-makers understand trade-offs between different scale-up scenarios.

In Niger, for example, following a full review of the available risk data, the government adopted the Water Requirement Satisfaction Index as its index for monitoring drought conditions and for determining when those conditions are severe enough to trigger the scale-up of safety net programs. The team next used data and analytics to build a tool that helps calculate both the number of potential additional beneficiaries and the costs of a scale-up over time. Actuarial techniques were then used to turn this historical cost into an understanding of the potential future costs then used to inform the money-in strategy. (See figure 2.)

Figure 2. Historic Cost of Scale-up Using Data from the Water Requirement Satisfaction Index for Communes in Niger

However, caution over the power of triggers is needed because a single trigger will not perfectly correlate with the conditions on the ground (technically referred to as basis risk). A robust system must be designed around any primary trigger to ensure there is flexibility in the plans and finance to respond even if the primary trigger is not met. Such a process is used in Uganda’s scalable safety net where a secondary and more flexible trigger is based on food security data and is used by an interagency technical committee to determine if a scale-up of the safety net is needed despite no initial primary trigger.

2. Pre-identifying Beneficiaries

By using exposure and historical loss data, analytics can support identification of areas that are most likely to be affected by future disasters. The data can be combined with data about welfare to understand who is the most vulnerable.

Once identified, the systems can be put in place to ensure that the beneficiaries receive a payout when a scale-up is triggered. This approach increases the speed of response and provides some clarity to communities as to who is and isn’t eligible.

During COVID-19, registries of potential SP beneficiaries were expanded to include newly affected populations such as urban communities. In Malawi, the government is implementing the emergency COVID-19 Urban Cash Intervention to poor and vulnerable households. This intervention is piggy-backing on the existing systems of the Social Cash Transfer Program, which is a flagship social protection program in Malawi. Through geographic targeting at hotspot locations for the first time, urban households have been uploaded into the Unified Beneficiary Registry and transferred to the Social Cash Transfer Program Management Information System.

3. Effective Payment Systems

How funding reaches beneficiaries is as important as how funds are secured in the first place, and so up-front investments payment systems are critical. The stronger the existing systems for delivering benefits, the higher the potential to use them in times of emergency. There is much to learn from the payments and claims management processes of the private sector.

Recent experience shows that e-payment digital technologies such as mobile money provide a faster and transparent mechanism to disburse cash for both regular and emergency programs. In Kenya, there is nearly 100 percent coverage of bank accounts in the counties covered by the Hunger Safety Net Programme. This coverage means that the systems could be leveraged to make a payout to almost all of the population were such a payment required.

How DRF Strengthens the Money-in Process

Once you have a model for the likely costs of scale-up a strategy can be developed for how to finance this.

4. How to Put in Place the Right Financial Instruments

No single financial instrument can address all risks. Governments should use different instruments to protect themselves against events of different frequency and severity (risk layering). With respect to ASP, this means different levels of scale-up. Figure 2 (shown earlier) highlighted the potential volatility of budget needs for scale-up. Managing budget volatility is a challenge for ministries of finance, and the ministries can use techniques similar to those used by insurance companies to manage this risk.

Through the right mix of instruments, governments can not only rapidly mobilize finance in the face of a shock but also can do so at a much lower cost, as highlighted in figure 3. By layering different types of financing—including reserves and contingent finances—governments can refrain from costly and slow budget reallocations and can reduce their dependence on slow and unreliable humanitarian appeals.

Figure 3 shows an example of a comparison analysis to inform a government about the most cost-efficient mix of instruments to ensure adequate resources to finance the scale-up of its safety net against once-in-10-year events. In this case strategy A is the most cost-efficient.

Figure 3. Example Assessment of Risk Financing Strategies for Safety Net Scale-up

Summary

DRF helps strengthen the transparency, predictability, and effectiveness of spending while protecting the constrained fiscal space. The Disaster Risk Finance and Insurance Program partners with the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice to integrate ASP into finance ministers’ broader DRF strategies.

With a DRF approach, the following occurs:

- The decision to trigger a response happens as soon as possible following a shock or before communities are severely affected by its negative impacts.

- Actors are more inclined to act early because the benefits of early action are acknowledged by all and assistance to affected communities is provided on time.

- Through the right mix of instruments, governments can rapidly mobilize finance at a much lower cost.

Photo Credit: World Bank / Sambrian Mbaabu. Market place in Kenya in April 2020.

To view this blog in a MailChimp setting, click here.

Disaster Risk Finance | COVID-19 Blog Series

- Five Lessons on Disaster Risk Finance to Inform COVID-19 Crisis Response

- Five Reasons You Should Be Thinking About Compounding Risks Now

- Five Reasons the Global Risk Financing Facility Is Relevant During an Ongoing Pandemic

- Five Ways COVID-19 Leads to Natural Catastrophe Protection Gaps at the Sovereign Level

- Expect the Unexpected: Three Benefits of Rainy Day Funds

- Five Ways the World Bank’s IDA-19 Is Supporting the Poorest Countries in the Time of COVID

- Three Ways That Contingent Policy Financing Contributes to Resilience Building Before, During, and After COVID-19

- Five Reasons to Support SMEs So They Can Build Stronger Resilience to Future Disaster Shocks

- Three Reasons the Public and Private Sectors Are Stronger Together Against Disasters and Crises

- Five Ways Satellite Data Can Help Prepare for the Unexpected

- Four Ways Disaster Risk Finance Strengthens the Effectiveness of Adaptive Social Protection

- Three Ways to Enhance Online Knowledge Exchange During the COVID-19 Pandemic