Five Reasons You Should Be Thinking About Compounding Risks Now

We are in the midst of an unprecedented crisis. To date, more than 435,000 people have tragically lost their lives as a result of COVID-19. The June 2020 edition of the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report forecasts a 5.2 percent contraction in global GDP in 2020—the deepest global recession since World War II and the broadest collapse in per capita incomes since 1870, thereby tipping millions back into poverty. Such global statistics barely capture the effects on the lives of people around the world.

It feels unnatural to think about future risks and disasters right now in the context of such unprecedented adversity and uncertainty, so why and how should we be thinking today about planning for future risks?

Reason 1. While economies slow down, disaster risk ramps up.

When one of the world’s largest purveyors of catastrophe risk models tells you that “you don’t need a cat model to know that there will likely be a meaningful disaster somewhere in the world this year" it is time to pay attention.[1]

The triple shock of COVID-19—health, economic, and financial - leaves people and businesses far more vulnerable to other shocks and stresses such as droughts, storms, floods, and food insecurity. Households and firms are less financially secure, and in some areas already suffering from food insecurity or compounding health effects as health systems are under strain. With government fiscal stimulus spending soaring and revenues falling, the fiscal capacity to respond to other shocks has shrunk. Credit—a key lifeline in crises—may be restricted. The capacity to absorb and respond to other shocks at all levels of society is more limited. Taken together, this reaction means that disasters strike even harder, and their negative impacts persist for longer durations.

When two or more risks interact, the potential collective effect can be greater than the sum of its parts - we describe this as compounding risk.

When thinking about future risks, timing is critical. In many emerging and developing economies, COVID-19 cases may not peak for several months, and the full economic and social effects of the crisis may not come for some time. Over this period, those countries will be particularly vulnerable to drought, floods, storms or other shocks.

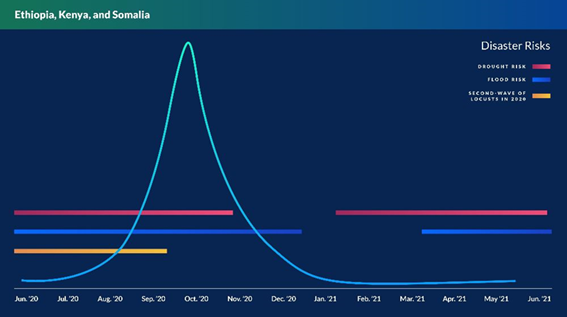

The Horn of Africa region provides an example. With well over 22 million people already food insecure in the region, and agriculture damaged from several months of locust infestations, the region is already suffering. Moreover, COVID-19 cases are increasing (as of June 18, there are 10,500 confirmed cases and 258 deaths) and economic projections predict a slowdown this year (5.8 percent in Ethiopia, 3.9 percent in Kenya, and 0.6 percent in Somalia).[2] Adding a major drought could be catastrophic.

Current projections for the Horn of Africa suggest that the peak drought and flood risk could likely coincide with the peak of COVID-19 cases. In Kenya, drought alone reduces economic growth an average of 2.8 percent every year[3]. As these risks compound so do risks of short-term threats, such as instability and internal displacement of people, as well as longer-term impacts on lives and livelihoods, poverty alleviation and growth.

Figure 1. Timeline of Peak Disaster Risk and Potential Peak of COVID-19 Infections in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia

Source of Modeled Scenario for Potential COVID-19 Infection Numbers: Metabiota

Reason 2. The future is uncertain, but the benefits of preparedness are clear.

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it is that there is no substitute for preparedness.

Countries that were better prepared have acted earlier and fared better. Countries already equipped with shock-responsive safety nets and financial shock absorbers, such as contingency budgets and contingent credit, have been more able to protect their economies and to ensure that if the worst happens, they can immediately protect their poorest citizens.

Social protection systems have been shown to be critical. To date, 195 countries and territories have planned, introduced, and adapted social protection systems in response to COVID-19.[4] Malawi’s government, for example, has quickly reconfigured its cash transfer program to include an urban intervention that will help fulfill the financial needs of the poorest citizens who are negatively impacted by COVID-19.

It’s also important to think about finance. When fiscal space is limited and there are immediate pressures on budgets, it can be easy to deprioritize financial preparedness for future risks, but preparedness is needed more than ever, both to the reduce short-term shocks and avoid long-term impacts on poverty alleviation and economic development. Having in place an effective strategy for disaster risk financing gives certainty that financial resources can be available when needed and at the lowest cost possible.

Just this year, for example, St. Lucia transferred more of its natural catastrophe risks to the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility to alleviate fiscal pressures in the aftermath of a disaster. Nepal pushed ahead with its first Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option (Cat-DDO) of $50 million - a line of contingent financing that provides immediate liquidity to countries to address shocks related to natural disasters and/or health-related events. The German government provided 19 million euros to protect up to 20 million poor and vulnerable people in Africa against drought using cover offered by African Risk Capacity. This can provide vital financial protection in a drought.

Reason 3. Keep an eye on the Pacific; cold seas herald a perfect storm.

Financial preparedness is particularly important for those countries that regularly face seasonal, weather-related risks. Although we can’t predict individual events, weather patterns enable us to know where and when they are most likely to occur. By combining data on seasonal cycles, seasonal forecasts, and preexisting economic and financial vulnerabilities, we can identify potential hot spots of risk over the coming 6–12 months.

Map 1. Compound Seasonal Weather and COVID-related Financial and Fiscal Risks

Note: Darker coloring denotes greater vulnerability.

Source of Seasonal Forecasts: UK Met Office, Department for International Development.

We are also keeping one eye on the Pacific Ocean. There are early signs of a La Niña developing later this year. This would mean a more active hurricane season for the Caribbean and Central America, a heightened risk of drought in the Horn of Africa, and an increase in the landfall of typhoons in Southeast Asia.

The hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean has already started early (there were two named storms in May) and food insecurity across many regions is already under stress. To improve financial planning and preparedness, the Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Program (DRFIP) is working with universities and pandemic modeling firms to better understand how disasters interact with ongoing stresses and co-develop new tools to support our clients to manage such risks.

For countries in such higher-risk regions, monitoring risks, revisiting plans and having financial protection in place is even more important than ever.

Reason 4. Now is the time to plan for a more resilient future.

Looking ahead to the recovery phase, we find an urgent need to embed stronger preparedness and resilience into policy, investment, and development finance. Now is the time to integrate resilience firmly into COVID recovery plans.

The social protection sector provides important lessons for managing future risks. Linking risk financing to shock-responsive safety nets, as Kenya and Uganda have done and as Malawi, Sierra Leone, and countries across the Sahel are planning to do, can be a game changer for resilience. These same principles can be used to strengthen the shock-responsiveness of other critical sectors, such as health, nutrition and education services, or integrate ‘financial shock absorbers’ into vulnerable economic sectors.

Our experience of embedding disaster risk financing in social protection programs has highlighted three important factors for success. The Global Risk Financing Facility is now supporting clients to build these lessons into other critical sectors.

Reason 5. Rise of the super cat: a new risk paradigm

The negative impacts of the COVID-19 crisis have been unprecedented; arguably, the speed and scale of its progression has taken many by surprise. We nonetheless know that this type of cascading, complex, systemic shock is becoming more common in our globally interconnected world. Super cats—systemic risk events—are here to stay. Climate change and growing pressures on resources and the environment add to the risk. Although our immediate concern is to protect countries during this crisis period, we also need to think about how to tackle these risks for the future.

Financial preparedness is even more important in this new risk paradigm, but we need a new tool kit to fully understand and quantify the new risks. Many institutions around the world are trying to tackle this same problem, and there are advantages to working together to share knowledge. DRFIP is currently working in more than 60 countries to help strengthen their financial preparedness and the first step is to understand our clients’ needs as we jointly develop new tools and approaches.

We also need to track those compounding risk factors that could make things worse right now, such as changes in global food prices and reduced remittance flows. The DRFIP is supporting World Bank efforts to develop a system for risk surveillance to support countries to better plan and prepare now, but also over the long-term.

We do not yet have all the answers, but we do have the questions. For example, is there a role for pandemic risk insurance pools? How can we use the principles of risk financing to better protect small and medium enterprises and firms from future shocks? What role can new sources of data such as remote sensing and machine learning play? And how can we leverage existing facilities such as the Global Risk Financing Facility to support our clients to manage their risks in this new risk paradigm?

We will be exploring those and other questions as part of this blog each week.

[1] https://www.rms.com/blog/2020/05/26/pandemic-plus-quantifying-potential-compound-impacts.

[2] https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects.

[3] Kenya Post-Disaster Needs Assessment, 2008-2011 Drought

[4] https://www.ugogentilini.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SP-COVID-responses_June-12.pdf.

Photo Credit: Unsplash. Volcano ash cloud in Mount Sinabung, Indonesia

To view this blog in a MailChimp setting, click here.

Disaster Risk Finance | COVID-19 Blog Series

- Five Lessons on Disaster Risk Finance to Inform COVID-19 Crisis Response

- Five Reasons You Should Be Thinking About Compounding Risks Now

- Five Reasons the Global Risk Financing Facility Is Relevant During an Ongoing Pandemic

- Five Ways COVID-19 Leads to Natural Catastrophe Protection Gaps at the Sovereign Level

- Expect the Unexpected: Three Benefits of Rainy Day Funds

- Five Ways the World Bank’s IDA-19 Is Supporting the Poorest Countries in the Time of COVID

- Three Ways That Contingent Policy Financing Contributes to Resilience Building Before, During, and After COVID-19

- Five Reasons to Support SMEs So They Can Build Stronger Resilience to Future Disaster Shocks

- Three Reasons the Public and Private Sectors Are Stronger Together Against Disasters and Crises

- Five Ways Satellite Data Can Help Prepare for the Unexpected

- Four Ways Disaster Risk Finance Strengthens the Effectiveness of Adaptive Social Protection

- Three Ways to Enhance Online Knowledge Exchange During the COVID-19 Pandemic